Context

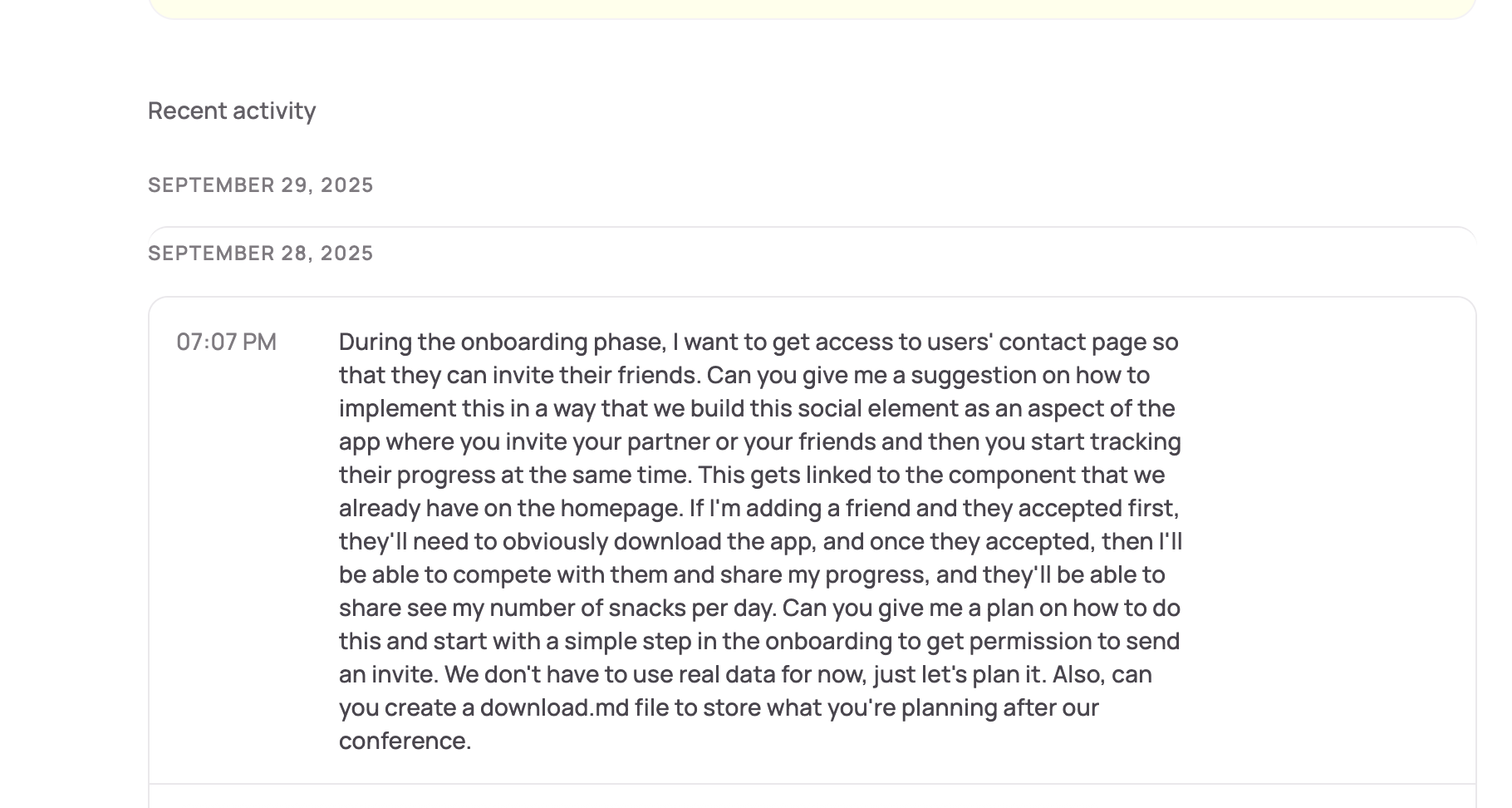

Okay Shahi, why are you vibe coding an app?

Honestly, I just missed building. I’ve spent years designing for growth, revenue, and ads, but there’s something magical about starting from scratch again. No briefs, no roadmaps. Just curiosity and a problem I actually have, I snack too much.

Problem statement

Habit formation. Retention. Motivation. I’m fascinated by apps that are tackling this area. It’s wild how technology can shape our behaviour how a single streak, sound, or a digital character can quietly influence our routines. It’s not just design anymore, it’s psychology wrapped in pixels.

But most habit apps feel a bit too serious. Calorie counters, graphs, reminders, all optimized for discipline, not delight. I wanted to explore a softer side of behaviour change, something that uses play, emotion, and curiosity instead of pressure.

At the same time, I’ve been experimenting with AI tools Claude, Gemini, Midjourney, Elevenlabs, Cursor and wondered: what if I combine the two? A personal goal to form better habits and a creative goal to test how AI can help design, code, and ship an app end-to-end.

That’s how Snack Monsters started. A playful way to explore habits, gamification, and the joy of building again.

Business My goals

Okay, so there are so many apps out there that are trying to achieve the same thing. and I'm not gonna lie, some of them are beautifully design. While researching this idea, I came across Atoms, the official Atomic Habits app. Mind blown. It has a beautiful onboarding, amazing typography, and great features.

I didn’t want to build another habit tracker that shames you for missing a day or celebrates you with fireworks for drinking a glass of water. I wanted something more personal, something that makes you smile even when you fail. The goal wasn’t perfection. It was consistency with delight. Plus, I never wanted to beat existing products but to understand how far prompting, prototyping, and iteration could take a small idea in just a few weekends.

Planning

Planning started with a PRD. Except this time, I didn’t write it alone. I debated it with multiple LLMs to shape the idea from different angles. How it should look, what features actually matter, and how to make it fun.

I started copy-pasting outputs from different prompts and basically turned it into a debate between them. Claude would suggest one approach, Gemini would challenge it, Grok would simplify it, and ChatGPT would fill in the gaps. Watching them argue ideas back and forth was surprisingly useful. It helped me see blind spots, mix perspectives, and land on something that actually made sense.

MVP MVP MVP

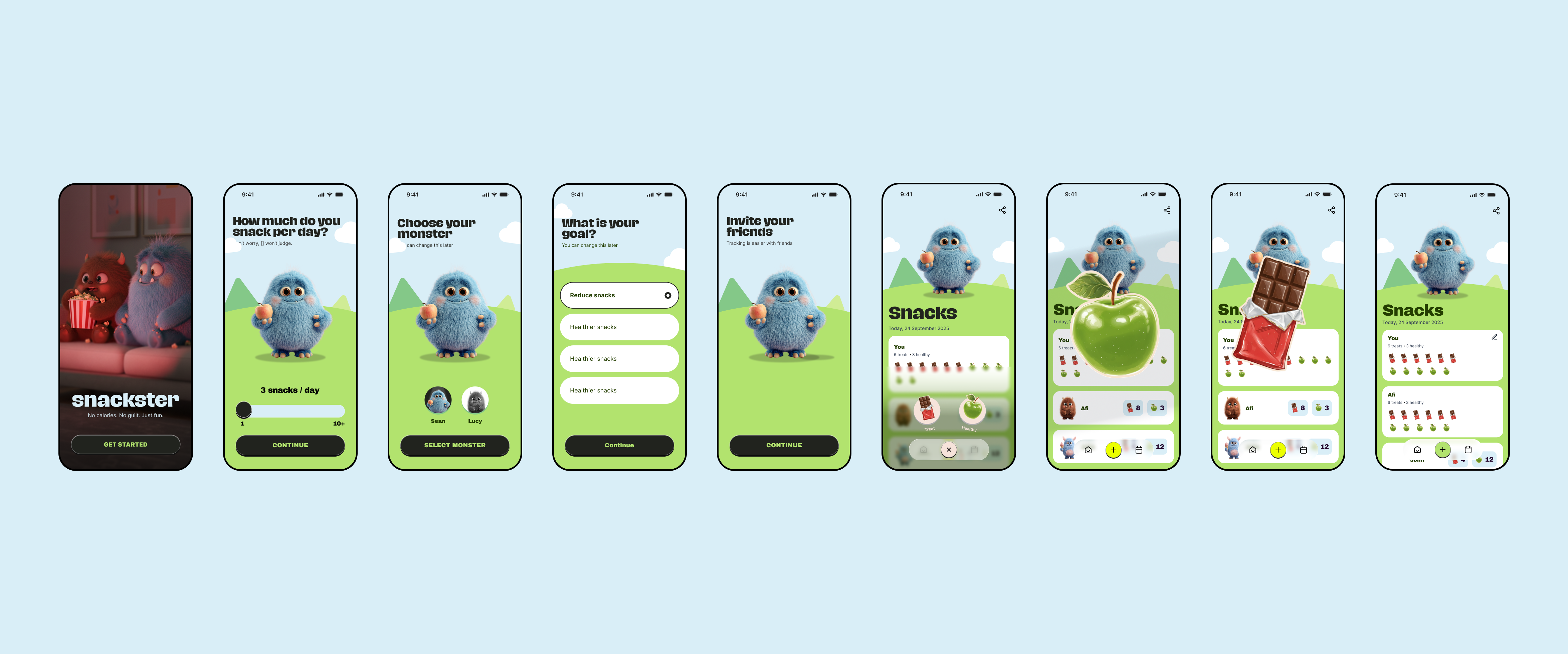

The tricky bit with becoming good at prompting and building + having a blank canvas is that you can quickly over-engineer and complicate things.

So I decided to do the bare minimum, just enough for my girlfriend and I to test and see if it makes sense. The first version had only the essentials: a basic counter, a growing monster, and a quick way to log snacks. No animations, no fancy logic. Just enough to play with the idea.

I realised we could easily change and improve things later once we actually saw it working.

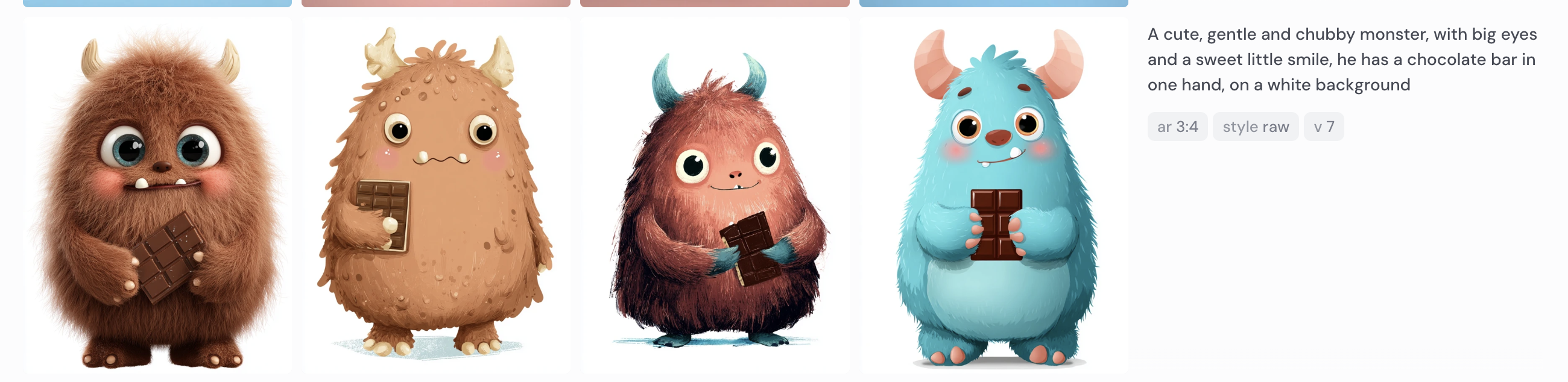

Meet Choco the monster

If I say Duolingo, the first thing that pops into your mind is language. The second is probably their bird, Duo. They’ve done an amazing job with character design and emotional attachment. There’s a great talk by Jackson Shuttleworth, Duolingo’s retention PM, on how that character consistency drives long-term engagement.

So I wanted to build something similar.

For this, I used Midjourney and Google Gemini. Midjourney was great for finding the vibe. I explored “cartoonish 3D monster characters” and tried a bunch of moods. Once I landed on a few I liked, I used Gemini to remix and fine-tune them, adjusting snacks, expressions, and scenes.

The prompt I used:

A cute, gentle and chubby monster, with big eyes and a sweet little smile, holding a chocolate bar in one hand, on a white background.And that’s how Choco was born. It was love at first sight.

I repeated this process to choose the other Crumbles. and then combined this to create other scenes and variations of the two monsters.

Behavioural design and gamification

If used well, gamification can genuinely drive positive behaviour change. I’ve always been fascinated by how small feedback loops and visuals can influence habits.

Snack Monsters builds on self-determination theory, autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Users choose what to improve, see progress, and feel good about it.

1. Self-determination theory (autonomy, mastery, purpose)

people stick with habits when they feel in control, see progress, and have a reason to care. snack monsters taps into all three:

autonomy: users decide what habits they want to track (snacks, water, reading, sleep).

mastery: progress is visualized through the monster’s evolution, each small win feels visible.

purpose: competing with your partner adds social meaning and accountability, but still feels light and fun.

2. Feedback loops (immediate cause → visible effect)

when you log a snack or action, the monster reacts instantly — grows, shrinks, or changes mood. that’s a tight feedback loop, the core of most successful gamified systems (think Duolingo’s streak or Apple Fitness Rings). it makes progress feel tangible.

3. Variable rewards

not every interaction should feel the same. unpredictability keeps people curious and motivated.

for snack monsters, that could mean:

the monster reacts differently each time (animations, sounds, expressions).

small surprises or easter eggs after consistent streaks. this builds a variable reinforcement schedule, one of the strongest behavioral motivators (used in games and habit loops).

4. Social competition (friendly accountability)

allowing users to invite a partner and compete adds a social layer that strengthens motivation through social proof and relatedness. you’re not just tracking a habit alone, you’re in a playful rivalry. even subtle nudges like “your partner just logged a healthy meal” can boost engagement.

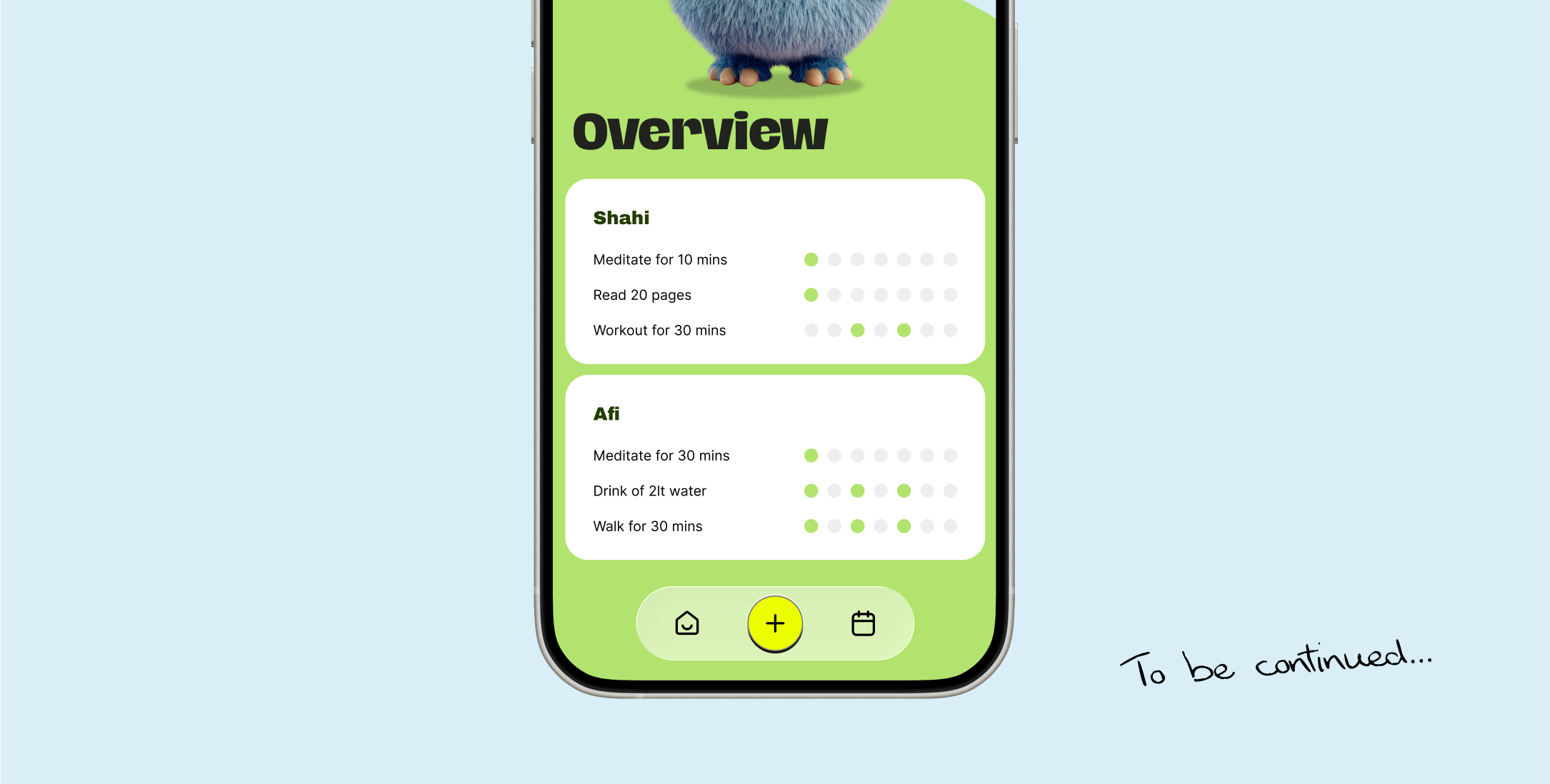

Designing the UI

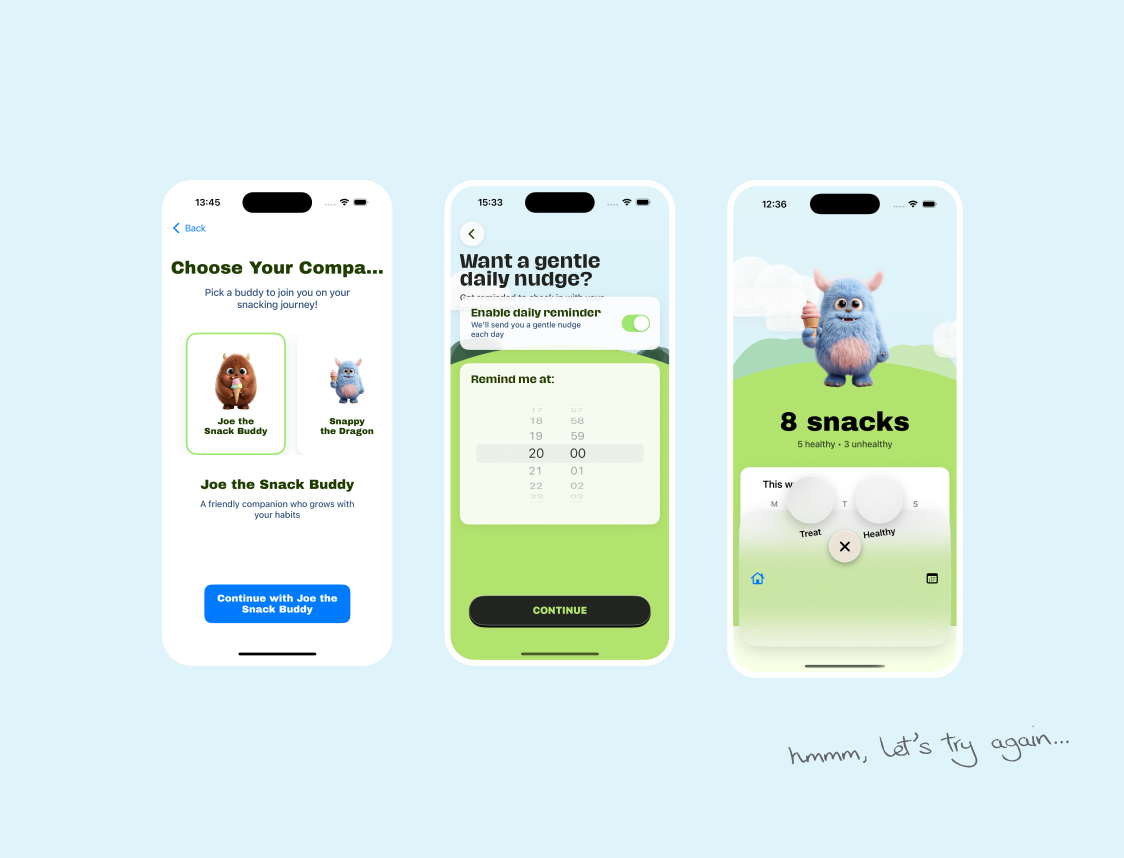

For the UI, I wanted something simple, playful, and lighthearted. Inspired by Tamagotchi, I started experimenting with different versions to see what could scale and still feel fun.

I built everything in SwiftUI, breaking it down into modular components like MonsterCard, SnackList, and SnackButton. This made it much easier to tweak visuals without breaking layouts.

Before jumping into code, I did high-fidelity mockups in Figma first. This helped me see the exact flows and build everything intentionally. Keeping things high-level at this stage allowed me to move fast without overthinking.

I’ve realised that for generic stuff, Claude can actually do a solid job at adding details of a flow, different states, handling empty cases, and so on, which helps me iterate much faster.

Okay, but how do you get the exact look and feel that you started with in the app? The answer is much simpler than it sounds. I’d just start screenshotting or copy-pasting the mockups directly into Cursor or Claude Code (both work), depending on what I was using. A lot of the time, they’d get surprisingly close to the original design. I’d only need two or three small tweaks to make it perfect. Sometimes the positioning would be completely off, so I’d ask Claude to point me to the correct file, open it, and manually tweak it myself. It turned out to be a super quick loop, mostly just screenshots, prompts, and a bit of back-and-forth with the models.

And if I wanted something very detailed, like the subtle 3D shadows on the buttons, I’d switch to Figma’s Dev Mode, copy the SwiftUI code directly from there, paste it into Cursor, and ask it to bake that into the component. That way, I’d (usually) get a perfect one-to-one match of the exact look and feel from the Figma component.

Once Claude gets the vibe and you’ve already built the structure, you can easily apply the same styling to other screens. For example, I was able to one-shot a new onboarding step just by explaining it and making sure it used the same components.

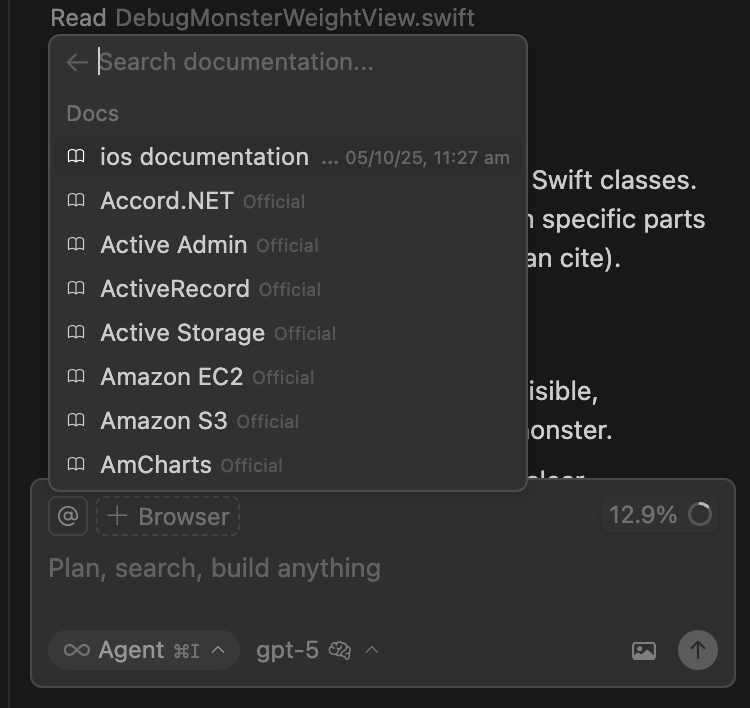

Let's get technical

I missed the fun of building or “vibe coding” as they call it nowadays. and I really wanted to build with swiftUI again. It’s been 9 years since I last opened Xcode (I feel ancient!!! ).

I used Cursor as my main IDE while running Claude Code in the terminal. That setup gave me a really fluid workflow. I could write, test, and iterate quickly while having Claude debug or explain things in real time.

What worked best for me was starting small and explaining context to Claude first before writing code. Instead of worrying about the logic of how monsters gain or lose weight, I started with placeholders, built the visuals, and only later added functionality. It’s much easier to iterate that way.

I also learned that building in components is key. It scales nicely and keeps layouts clean.

I realised it’s not always great at following best practices compared to how it performs with frameworks like Next.js so one thing that really helped was linking the official iOS documentation directly in Cursor. Having the docs connected made a huge difference, it helped stay consistent when generating SwiftUI components and follow proper Apple patterns instead of making things up.

I also tried OpenRouter.ai to connect different LLMs and compare how each responded to the same task, super helpful when fine-tuning the tone or code style between models.

Most of the time, I’d experiment with a few Claude tricks too:

running

claude --dangerously-skip-permissionswhen I wanted it to scan files and docs freely without asking for permission each time (use carefully).using

claude -rto continue a previous conversation or debug flow.testing the new

/security reviewcommand, which Claude recently launched to automatically scan code for vulnerabilities.

Together, these made the workflow feel surprisingly fluid, almost like coding with a team of AI assistants that each had their own strengths.

For prompting, I used Wyspr Flow. It's a game changer! It allows you to use voice for prompting. I can explain big ideas out loud, add context faster, and store the transcripts as markdown files to reuse later. It makes the whole process more natural and way faster.

Debugging

When it came to debugging, I kept switching between GPT-5, and Claude Code whenever I hit a UI issue. Sometimes it worked beautifully, and sometimes it got messy. They’d start changing random things in the layout or rewrite chunks of code I didn’t want touched. So every once in a while, I’d just discard the whole branch and start from scratch. It sounds painful, but honestly, it kept things clean and helped me iterate faster.

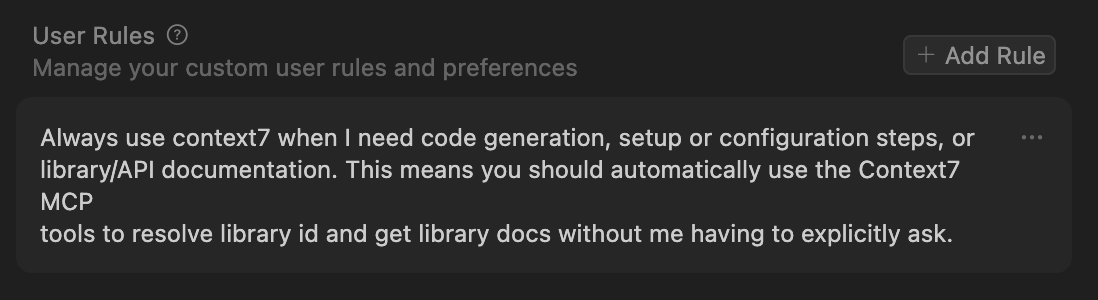

On the backend side, I used Supabase. And here’s where Microsoft's Context7 became super useful. It lets Claude directly read and modify the database in real time. So if a user reports a bug, I don’t have to manually log into Supabase and search for user IDs. I can just describe the issue, and Claude handles it instantly. Here is the custom Rule I used after setting up Context7.

Here are some of the early UIs it generated, rough, a bit chaotic, but you can already see the direction starting to take shape.

Outcome

Let’s talk KPIs, and success metrics, north stars. or at least pretend we’re being serious for a second.

How will I measure success? Well, I guess it’s not MAU or retention curves this time. It’s simpler:

did it make me (and my girlfriend) snack less?

did it make building fun again?

did I learn something new about AI workflows and behavioural design?

If yes, that’s already a win.

Technically, the MVP worked. The UI flows made sense, the monster reacted as expected, and we actually started using it daily for a couple of weeks. More importantly, it became a solid prototype for a bigger idea, one that could scale into a full habit-tracking system with competition, streaks, and AI-generated feedback loops.

And honestly? That’s my favourite outcome. It reminded me that small, scrappy projects can teach more than polished ones.

Next steps

Now that the MVP is working, the next step is to actually use it, test it over time, tweak it, and see what sticks. The goal isn’t just to track snacks anymore, but to turn this into a proper habit experiment. I want to test how consistent feedback, reminders, influence long-term habits.

I’m also planning to experiment with some of the latest updates in the tools I used:

Figma recently introduced remote MCP server + Code Connect, which allows you to bring structured design context, tokens, components, and metadata, directly into agents or IDEs, in my case that's Cursor. That could make the AI handoff (never thought I'd use this term) between design and code even smoother, helping Claude or Cursor understand component structure natively instead of guessing.

Cursor 1.7 is another big one. It now supports browser controls, meaning agents can screenshot, inspect, and debug the UI live basically making them an extra pair of eyes for your front-end. The new Plan Mode (where the agent writes a plan before acting) should help with longer, more stable coding sessions, and I want to understand how to use Hooks.

Add voices to the monsters with ElevenLabs. I want each monster to have its own personality and tone, playful, sleepy, dramatic so hearing them react when you follow a habi (or don’t) adds a new emotional layer to the experience.